A Prince Among Men

Why Iran’s Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi Wants Us to “Stop Hoping and Start Believing” in a Free Iran

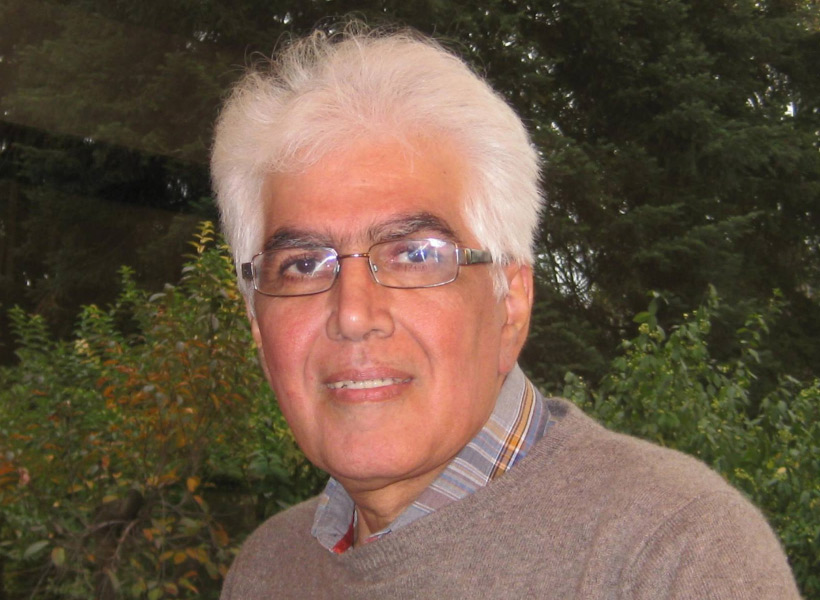

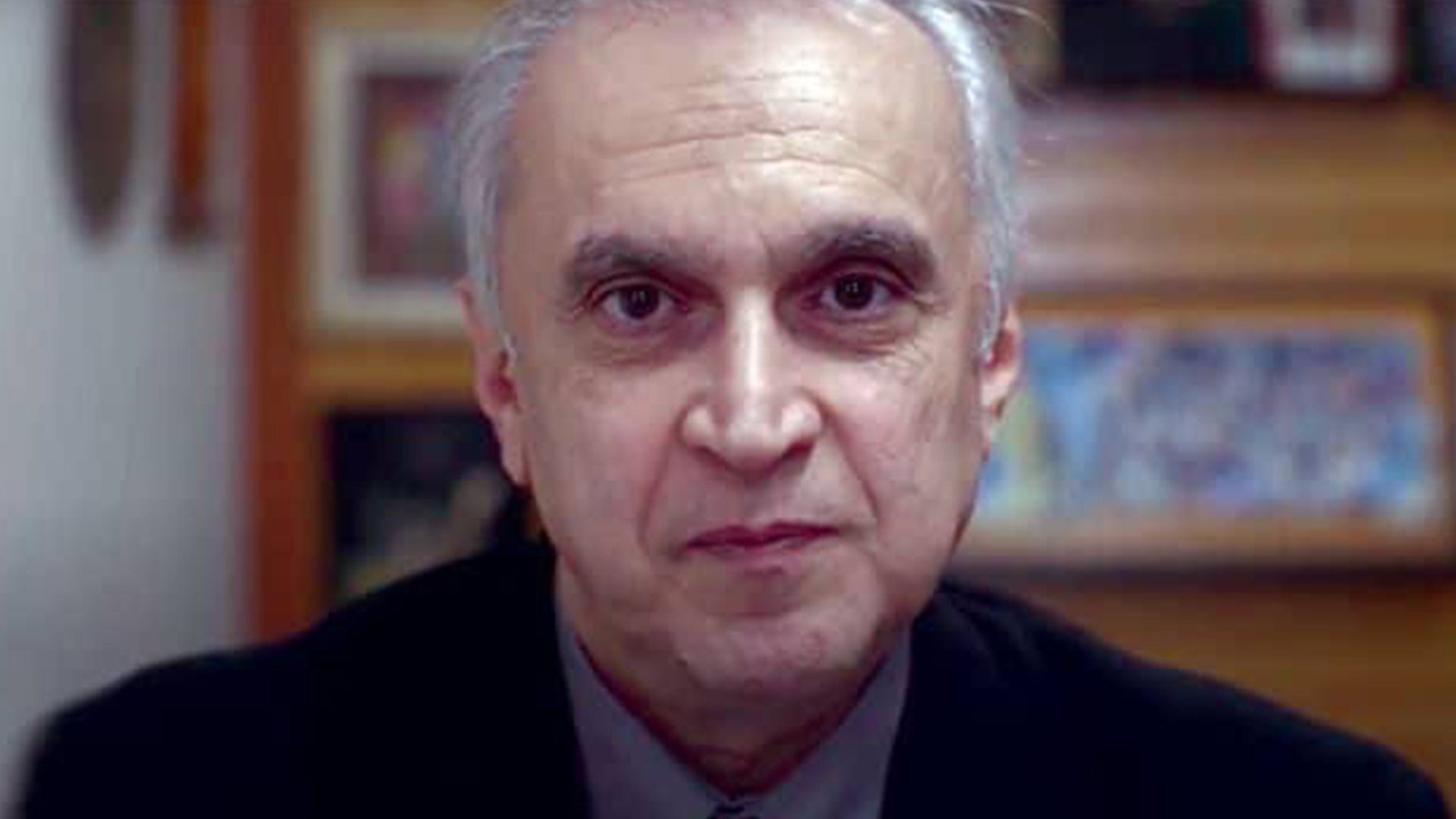

His Excellency Reza Pahlavi, the Crown Prince of Iran, shook my hand and awaited my questions in the sitting room at a suite in a West L.A. hotel, as guards stood watch at the door. His red, white and green lapel pin, in the shape of Iran, with the imperial emblem of a lion and a sun at its center, shone like a small jewel in an otherwise innocuous meeting space.

Dressed in a crisp, dark gray suit, everything about Pahlavi, from his subtle mannerisms to his stately posture and his tone of voice, evoke quiet regality and masculine grace. In a word, the man, whom millions still regard as best-suited to lead a free Iran, is princely.

I, on the other hand, reverted to a proverbial peasant as I realized that meeting Pahlavi completed a symbolic circle in my own story of escape from my former homeland. Speaking with the crown prince offered me a semblance of healing; the magic of Pahlavi is that he is recognized as a vital Iranian leader (albeit in exile), but is not a member of the brutal regime that has terrorized so many for over four decades. Pahlavi’s subtle habit of using phrases such as “my country” in referring to a state currently run by fanatic clerics endears millions of Iranians in the diaspora to remember that Iran is still, in many ways, our country as well.

And as our interview progressed, I realized that I carried the pride and pain of generations of family members with me to that well-secured hotel room. That may have explained why, at the conclusion of our interview, I informed Pahlavi that my “Nanechi,” a colloquial term of affection for my late paternal grandmother that loosely translates to “Little Mama,” would have been proud of me for having sat down with the crown prince. Pahlavi, in all his regal decorum, smiled endearingly; in his decades-long role as the exiled heir to the Iranian throne and the seeming savior of many who dream of a democratic and secular Iran, he has seen and heard it all.

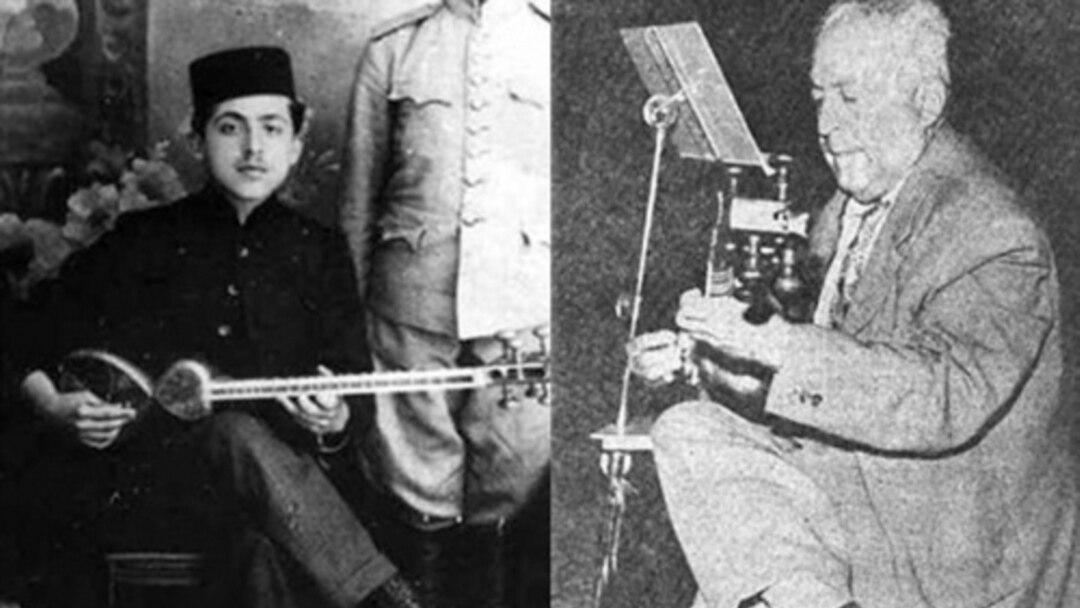

There is a subtle surreality in meeting a man who is the grandson of the legendary Reza Shah (who reigned in Iran from 1925 to 1941), credited with modernizing Iran to the degree that he was often compared to Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, and would have been crowned king in Iran in 1980, after the death of his father, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had the Islamic revolution not swept Iran in the late 1970s. Yes, Pahlavi was destined to be king, though he has long maintained that a post-regime Iran should be a democracy, whether it will be a republic or a constitutional monarchy.

It is worth asking how many descendants of pivotal, 20th-century leaders in the Middle East are wholly active and committed to the betterment of their homelands today, particularly from exile. Turkey’s Atatürk left no biological descendants, and the descendants of Egypt’s Anwar Sadat, while still expressing support of his vision for Middle East peace as private citizens, have not and will not lead Egypt. And while powerful leaders who sought nothing close to regional peace or modernization, such as Syria’s late Hafez al-Assad, may have produced an heir who currently rules the country, it is hardly a secret that Bashar al-Assad has managed to wreak utter havoc upon his homeland. Among the descendants of former giants of the Middle East, Iran’s Pahlavi, who currently resides in Virginia, stands seemingly alone.

A LITTLE GIRL’S ENVY

I had seen photos of Pahlavi, his late father, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (known as the Shah of Iran), and his resplendent mother, Empress Farah. Long before I was born, my mother had affectionately cut out magazine clippings of the Iranian royal family — her king and queen — and saved them in a special album. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 that ousted the Shah and his family and turned the country into an official Shiite theocracy run by an anti-Western and antisemitic cleric named Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the contents of that album became a liability. In the late 1980s, my mother begged me to not reveal to teachers and classmates that we were in possession of dozens of magazine clippings dating back to the late 1960s and 1970s featuring images of a bejeweled king and his stunning queen, who surely would have been executed had they remained in Iran after the revolution. Today, I realize that, as a teenager, my mother had excitedly searched for photos of the royal family the way teens worldwide pored over magazines in search of images of the Beatles.

Most little girls envy their mothers’ clothing and accessories, but as a six-year-old in post-revolutionary Iran, I envied neither my mother’s fabulous dresses, which she wore beneath her mandatory manteau (a long coat that, by law, had to cover her posterior), nor the heirloom necklaces that draped her elegant neck, which were always covered by her mandatory hijab (Islamic head covering). My compulsory hijab often matched my mother’s, though my head scarves also included fabrics laden with drawings of flowers.

No, I did not envy my mother’s dresses nor her jewelry; as a little girl in post-revolutionary Iran, I was plagued by relentless envy of my mother’s former governmental system. Why had my mother enjoyed a king, a queen and princes and princesses, but, having been born in the 1980s, I was subjected to the merciless power of an Islamist cleric who assumed the title of “Supreme Leader’” and who, along with his cronies, undid nearly all of the Shah’s historic efforts towards modernization? The Pahlavi dynasty was not without its fair share of criticism, but had it continued, Iran would have been on track to becoming the Japan of the Middle East; instead, it became the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, with an inflation rate of over 47% last year.

TURNING BACK HOME

On January 30, the night before our interview was scheduled, Pahlavi delivered historic remarks at the Museum of Tolerance at the Simon Wiesenthal Center in West Los Angeles. The invite-only event, which was organized by George Haroonian, a tireless Iranian American Jewish activist and founder of notoantisemitism.org, which educates Persian-language readers worldwide about Iranian antisemitism, also featured a candid conversation with Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean and director of Global Social Action Agenda for the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

As he entered the auditorium, the crown prince was greeted by exuberant shouts of “Javid Shah! Javid Shah!” (“Immortal King”). Some of the over 200 attendees, most of whom were Iranian Jews, told me that they still remembered the day when, in October 1960, Pahlavi was born and pre-revolutionary Iran erupted into celebrations as an heir to the throne was finally produced.

Seventeen-and-a-half years later, as an Imperial Iranian Air Force cadet, he would leave Iran to continue pilot training at an air force base in Texas. The following year, his entire world would change as the previously unimaginable unfolded: The Shah would leave the country; Iran’s military would be unable to quell a national revolution whose seeds had been planted by both the West and a Shiite cleric in exile and a powerful theocracy would soon arise in the Middle East. On Feb. 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini reentered Iran after a fifteen-year exile and the Islamic Republic of Iran that we know today was born.

Exactly 45 years later, at a historic talk at the Museum of Tolerance, Pahlavi repeatedly condemned Western “appeasement” of the regime, but began his remarks by specifically addressing the Iranian Jewish community in the diaspora. “When you see all of the hatred, and it feels like you have nowhere to turn and no place to call home, remember that you are part of the Iranian nation,” he said. “We, your fellow compatriots, share with you this home.”

Comparing the human rights abuses Hamas’ captives have suffered to what the ayatollahs have unleashed against Iranian citizens, including violence against women, Pahlavi stated, “When it feels like you have nowhere to turn, you can always turn home. And know that for anyone who seeks to divide us, Iranian from Iranian, as a secular democratic nation, we shall never permit it.”

“Home” is a complicated term for both the crown prince and his family, as well as for the millions of Iranians in diaspora communities all over the world. Pahlavi knows as well as anyone that there is no returning home until the regime changes. Such a feat would not only free nearly 88 million Iranians, but usher in an extraordinary new era of peace in the Middle East, precisely because it would leave Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis in Yemen and other fanatic terrorists in the region without funding, training or support. Among anti-regime circles outside of Iran, a name has already been suggested for a future peace deal between Israel and a new Iran: the Cyrus Accords.

In April 2023, Pahlavi and his wife, Princess Yasmine, made a historic visit to Israel, arriving for the Jewish state’s official Yom Hashoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day) commemoration. Seemingly everywhere the royal couple went, the old, Iranian Imperial National Anthem was played, and the trip included many hugs and flowers from Israelis. After a visit to Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Center and the Western Wall, Pahlavi coupled two of the world’s most enduring ancient communities — Jews and Persians — by invoking the name of the Zoroastrian founder of the Persian Empire. He tweeted, “2,500 years ago, Cyrus the Great liberated the Jewish people from captivity and helped them rebuild their Temple in Jerusalem. It is with profound awe that I visit the Western Wall of that Temple and pray for the day when the good people of Iran and Israel can renew our historic friendship.”

A SHARED FATE

Pahlavi and I sat down for an interview just days after three American troops were killed and over 30 injured in a drone attack by Iranian-backed militias, prompting even greater escalation between the United States and Iran in the wake of Iran-backed Houthi attacks against commercial vessels in the Red Sea. In early February, the U.S. responded to the attack in Jordan by conducting strikes on over 85 targets in Iraq and Syria that were linked to Iran. Weeks earlier, Iran had amped up its satellite and rocket programs by successfully launching the Soraya satellite with a three-stage rocket. The launch prompted worldwide concerns that the regime was testing whether it could outfit ballistic missiles with nuclear weapons, as part of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRCG) space program. Iran was also engaged in a series of tit-for-tat attacks against Pakistan.

But given that the regime helped Hamas plan and execute the Oct. 7 massacres, I began the interview with Pahlavi by discussing Israel. The following has been condensed and edited for clarity and space.

Jewish Journal: We know that there is a difference between hearing that another country is under attack, without having visited there and established a personal connection, versus having seen that country with our own eyes. How did your first-time visit to Israel last April personalize the tragedy of Oct. 7 for you?

Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi: Well, the first victims of this regime are Iranians, in terms of [the regime] immediately bringing in an element of despising and hatred, calling America “The Great Satan” and Israel “The Little Satan.” So the immediate consequences were that Iranians were the first hostages of this regime, and the Jews and Israelis have been the immediate follow-up victims. It puts us on the same road. So there’s a commonality of being hurt by it, which leads to the combination of the solution to it.

JJ: Can you elaborate on that solution?

“No countries are more tied, in their fates being sealed with one another, than Israel and Iran are right now.”

RP: No countries are more tied, in their fates being sealed with one another, than Israel and Iran are right now. Over 40 years of the Islamic Republic has proven time and again why the relationship is so vital in terms of strategic interests. What is important is not so far as the 21st century right now, and how we look at things in the modern era, but when you think about the biblical relationship and how unique that is. I don’t think there are any two countries on the planet that go back more than 25 centuries [as do Iranians and Jews].

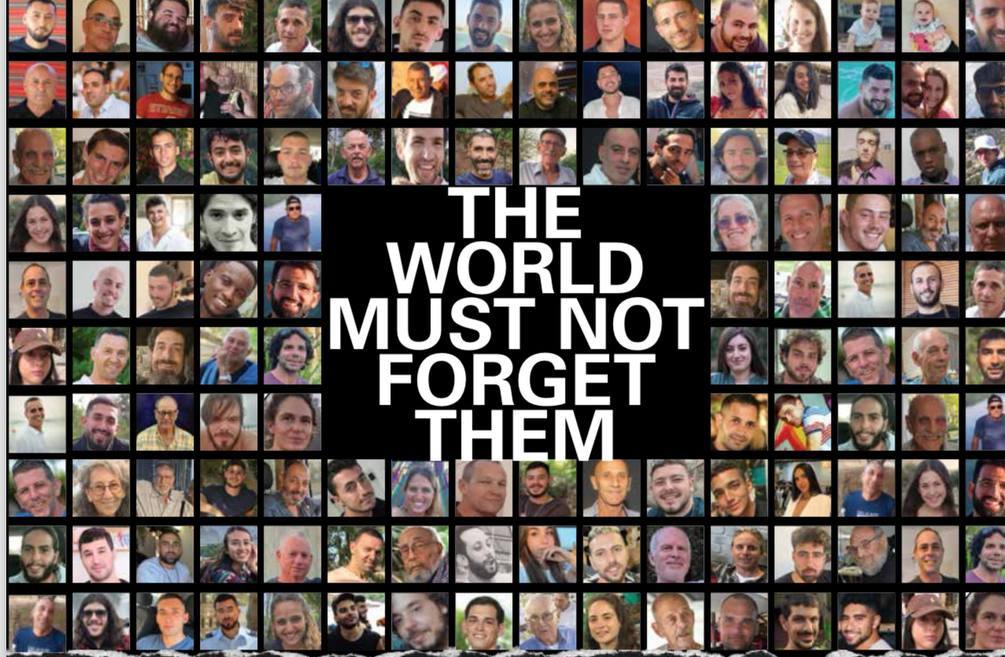

At a time when half of the world wasn’t even on the map, that’s very important. Of course, you detect that. You sense how Iranians are in pain when they hear about the young [Israeli] women being first raped and then executed. You see, this massacre was based on complete hatred. And when you see these images, there is so much empathy. Of course, I was there [in Israel last April]. I talked to average people on the streets.

JJ: What messages did Israelis convey to you?

RP: I heard their sentiments and how they viewed a different world. Clearly, that affected me very much in the sense that now, we can understand the importance of standing up to the common enemy that we have, because as long as they are around, we will not see a moment of tranquility that’s conducive to peace. As long as they have warmongers sabotaging every aspect of bringing normalcy and cooperation, what do we expect? Iran knowingly supported the Oct. 7 massacre because they wanted to sabotage the Abraham Accords, but the regime is not the people. One of the reasons I wanted to go there [Israel] was to tell not just Israelis, not just Jews, but the whole world that we [Iranians], as the children of Cyrus the Great, have a completely different outlook about how the region can be, especially the relationship between my country and Israel, and what will be in the future. It is totally the opposite of what this regime has been trying to portray.

JJ: During your visit to Israel last April, you also met Rabbi Leo Dee, who lost his wife and two of his daughters, Maia and Rina, in a terrorist attack that same month. Can you tell readers about that interaction?

RP: There wasn’t much of a chance to have a discussion because we were there to offer our sympathies during a mourning ceremony. He was very much touched by my appearance because we were there, showing our sympathy for a victim and his family for such an atrocious attack, which was totally unjustifiable. But it humanizes the entire element, that beyond politics or the antagonism of this group or that group, on a human level, we’re all the same. It doesn’t matter what faith or what ethnicity we are. It was a human rights issue, first and foremost.

“We are neither in a war of civilizations nor a war of cultures; we are in a war of values.”

Of course, sometimes, tragedy occurs, but it only brings more importance to this value system. We are neither in a war of civilizations nor a war of cultures; we are in a war of values. Values such as human rights, liberty and non-discrimination of any form. That’s where we stand. As opposed to those who do discriminate against women, against ethnicities. That’s the contrast. That’s why Iranians have shown so much solidarity in recent months with Israel, more than ever before.

We need to make sure that those who claim they are supporting human rights or social justice align themselves on the right side of history. Here, you have a nation taken hostage by a regime for 45 years, and it’s not only repressed its own citizenry at home, but it’s brought violence and radicalism, and everything they do via their proxies in the region. So we are in this fight of values, what this regime stands for, and its sinister objectives, with those who share the same principles [as us]. We need to therefore be in solidarity, confronting this common enemy.

JJ: We know that many in Iran support freedom and view Israelis as their brethren, but how do you respond to Iranians who still consider Jews and Israelis as enemies?

RP: There are some who are committed to conflict; they are actually warmongers. When Jewish people say “L’Chaim,” what does that mean?

JJ: It means “To life.”

RP: And it means “we value life.” We value life. You look at Iranian poetry and culture, it’s also a celebration of life. But these people celebrate martyrdom. They actually encourage what we say in Farsi as “azah-daree” (“to be in mourning”). How much is that contrast, that negative darkness, of celebrating martyrdom as opposed to celebrating life?

JJ: The youngest person to have lived in a free Iran would be 45 years old today, old enough to have been an infant just before the 1979 revolution. Are you concerned that almost a half-century of regime propaganda and darkness have somehow created a wedge between the Iranian people and the history that you want them to embrace — the history of a time dating back to Persian civilization and Cyrus the Great?

RP: I remember a Turkish journalist who interviewed me a couple of decades ago who told me back then, “I think you Iranians are coming out at the other end of the tunnel. We [Turks] are just beginning to enter it,” in the sense of direct experimentation with a religious dictatorship, and the consequences of that. That was 20 years ago, when you did not have Instagram, TikTok or any of that. If you look at today’s Gen Z [in Iran] now, what’s happening is not so much what they remember from history, even though they are doing their own due diligence in research.

Even in modern days, when you look at where Iran was headed, it could have been by now the Japan of the Middle East; instead, it is the North Korea [of the region]. As I said last night [at the Museum of Tolerance], is it because we lacked resources or ingenuity and talent? It’s just a system that has been so poisonous and so negative.

We can realize our full potential yet again. But we are not doing this at all. There are Muslim countries that can come together, and we don’t need to look at it from the point of view of a zero-sum. It’s not that my gain is your loss. It should be a win-win approach. That mentality is beginning to instill itself.

JJ: Are such messages being conveyed to you by the people of Iran?

RP: In a lot of the DMs (direct messages) I get to my Instagram account, the younger generations keep saying that we have never witnessed that [older] Iran, but we have fallen in love with it. They have looked at the contrast; they see that sense of nationalism and patriotism that’s in the best interest of the nation, as opposed to the regime that lets people starve on the street. But the minute the regime gets more money, it spends it on the proxies that are going to attack Israel.

The generation of today, I think, is different from previous generations, because one thing that separates today’s Gen Z is that their predecessors, in the last 30 years, were trapped into the narrative of [former Iranian president Mohammad] Khatami and [former Iranian president Hassan] Rouhani and thought, “Let’s give reform a chance,” even though student leaders were being thrown off of the rooftops of dorms. And the world was fooled by the “reforms” as well.

“This generation isn’t buying into the narrative of giving reform a chance anymore. They are recognizing that their fate depends on this regime ending.”

Whereas today, people are beginning to point to the root cause of the problem being the [1979] revolution itself. That is a major shift and a revision of looking at the problem. This generation isn’t buying into the narrative of giving reform a chance anymore. They are recognizing that their fate depends on this regime ending. Common phrases I now see include “What did we give and what did we get in return?” [referring to ousting the Shah].

“The passage of time is like stepping away from a mountain. You cannot sense the magnitude of this mountain if you are at the foothills.”

The passage of time is like stepping away from a mountain. You cannot sense the magnitude of this mountain if you are at the foothills. But if you are 10 or 20 kilometers away, then you can see the whole mountain. Sometimes, it takes time for people to get a wider perspective of history. At the moment, they may not realize it. I speak with younger generations of Iranians in the diaspora, and if they know something [about pre-revolutionary Iran], it’s because their parents passed it on to them.

But the tools and data now exist that weren’t available to people before. In this modern age of communication, information and social media, we can no longer feign ignorance because it’s a matter of looking in the right direction. I’m optimistic about Iran’s future. I always say, “You can awaken those who are actually sleeping, but you cannot awaken those who pretend to be asleep.”

JJ: Last night, you repeatedly urged for the need to support the people of Iran, including assisting them financially if they engage in nationwide strikes against the regime. But we both know that this regime wants to stay in power, and has billions invested in maintaining that power and the infrastructure it has created for itself. The regime is not leaving without a fight. How do you maintain your belief that the regime can actually be removed by the will of the people, rather than by force or violence?

RP: Because I think that like any giant, there is, at some point, an Achilles’ heel. If you hit them somewhere that they have no remedy for, that’s where they lose. The first element in the strategy is to at least equal the playing field. That means if there’s a policy from a foreign government’s standpoint to address maximum support, including of course the private sector and the diaspora, you can increase the chances of success because you incentivize the people, because now they know that they have more means to challenge the regime.

“I never believed that the violent scenario of [regime] change is the ultimate solution, because you have to find a way to use means that justify the ends.”

I never believed that the violent scenario of [regime] change, by means of conflict and confrontation, is the ultimate solution, because you have to find a way to use means that justify the ends. I always had certain red lights that at least I am committed to.

I’ve been a student of Gene Sharp and the nonviolent civil disobedience movement, and I know people sometimes say that this regime is merciless. But I say, no. There has to be, at some point, a difference between us and them. Part of the reason you create the incentives for elements that may be right now in no man’s land, but they want out. I know there are members in the [Iranian] military and paramilitary forces that the bulk of them don’t believe in this system.

But they have to get their paycheck at the end of the day. You have to offer them an exit strategy. You have to be able to say that post-regime, they’re not going to be sent home; there’ll be a place for them. Sure, there are some who are really guilty in terms of the heinous crimes they have committed and they have to be answerable to Iran. There has to be some level of closure.

We need to understand that when we talk about regime change, that doesn’t mean that everyone in a post has to vacate it. I think that 80% of the existing bureaucracy will remain during the transition, because the country has to still operate.

JJ: What about the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), that is dangerously fanaticized, wealthy and powerful?

RP: I come from the viewpoint that you should not give them an excuse, in the sense that they will feel targeted, that they have no place to run; that they have to stand where they are, and justify even more repression, as opposed to “We are offering you a way out, side with the people, become their shield, come back to society.” I’m not naive, in the sense of thinking that they will all do that. But like everything else, you minimize the casualties.

We understand that in order to succeed, we have to overthrow this regime. But in the period of post-regime, you have to have a policy of national reconciliation and amnesty. That vicious cycle of “entegham” (“revenge”) is not part of my mentality. Rather than “entegham,” the best revenge is to be successful in our campaign, to actually bring in those values that were lost with this regime. To bring back equality. To bring back the family laws, the first laws that Khomeini eliminated, paving the way for the first victims of the regime to have been Iranian women.

Isn’t this the best way of proving ourselves right? But it’s based on reconciliation, on learning from our past. So we can respond to that Turkish journalist 20 years ago about where we are now.

You asked me about the Iranian people. When 9/11 happened, in most of the cities in the Middle East, half of the countries that were supposedly American allies were celebrating the al-Qaeda attack. The only [Muslim-majority] country where the people stood in candlelight vigil and sympathy were the Iranians. This is consistent with support that we see from Iran to the Israeli people, that is consistent with where the people [of Iran] stand, as opposed to the regime. The world needs to know that.

JJ: Did your late father offer you advice about statecraft and leading a nation?

RP: You’re not the only one asking this question. I’ve often been asked this question. The truth is that at the time I left Iran, I was only 17-and-a-half, I don’t recall ever having an opportunity to discuss that level of guideline with him. We never had those kinds of conversations. And right after my family left Iran and I regrouped with them, during our exile steps, his illness and state of mind was such that there was not so much of an opportunity to leave me with some kind of a roadmap. But I can tell you one thing: My father said, “The way that I had to operate was different from what my father [Reza Shah] did,” meaning my grandfather.

“My father said, ‘I am doing all this so that my son and his generation will inherit a different Iran, which will be very different from what I had to do in my timeframe.’”

My father said, “I am doing all this so that my son and his generation will inherit a different Iran, which will be very different from what I had to do in my timeframe.” So it’s not necessarily by having heard any advice, but by understanding that each era and circumstances requires its own way of seeing things. That’s a little bit the way I see myself generationally-speaking.

My grandfather took over at the time that Iran was in complete disarray. It was an underdeveloped country, run by the mullahs, we had no modern institutions of any kind. He had to bring in a centralized government, a modern army, you name it, just to begin to establish the status of a modern state. And as you know, he was very impressed by what Kemal Atatürk was doing next door in Turkey.

That was the pre-Second World War era. So my father stepped in right in the thick of it, towards the end of the war, and then, it became a matter of education, modernization, infrastructure-building and so on.

I think that my generation [had I led Iran] would have been challenged mostly by the following period: Now that we have the economic and development aspects of things, what about liberalization? We never came to that because we were going in that direction, but it was preempted by the revolution.

So where do we pick up where we left off? And in the meantime, what have we learned? And that’s not just me, Reza Pahlavi saying this. At my age, they call me “Father” now.

“Today’s Gen Z [in Iran] calls me ‘pedar [‘father’], which is very touching.”

Today’s Gen Z [in Iran] calls me “pedar” [“father”], which is very touching. But it also shows that at some point, you have to pass the torch to the next generation, and that’s the evolution of things. In that sense, I get much more direction from what the people want because no matter how you want to decide things or establish a viewpoint, the people have to stand to benefit from it. They have to buy into that vision.

And today, one thing that I have noticed is that most people say, “Now, we understand what he [the Shah] was trying to do. At the time, we didn’t.” So it’s important to make sure that from the get-go, people immediately understand what needs to be done, not 40 years later.

JJ: If you were afforded a chance to fly from Dulles Airport tomorrow and arrive in a free Iran, where would be the first destination that you would feel a personal obligation to visit?

RP: Clearly, it would be the most impoverished or afflicted areas of the country. The Baluchestan region is probably the first that comes to mind. Part of the reason for my trip to Israel was to talk about the water crisis. And as you know, water is one of the most important challenges that we face as a nation [in Iran]. We have to address it. There are areas in our country where the ground has been petrified. Even if you try to rehydrate it, you can’t, meaning that now, you have sand dunes that are beginning to engulf certain villages in that region, forcing relocation. Where would they go?

That’s why I’m bringing with me a whole host of experts. I would like to be able to do that, to tell the nation, “Listen, we are not only talking about motherhood and apple pie only. We can always talk about liberty, human rights and democracy. Of course, that goes without saying. But then, what’s our plan for recovery? What is the role of the diaspora? How many entrepreneurs can bring in new technologies and investments? What are the experts going to do about our environment? If we want to develop an industry of tourism, we cannot show them a whole bunch of dried-up lakes and polluted waters, can we?

How can legal experts talk about transitional justice right after the change of regime? How many economists are working with the short-term, first 100 days of the interim government and what needs to be done? It’s a whole package.

And whatever I end up doing, in terms of contributing to that, to bringing the cavalry to help, it’s understanding what challenges our country faces and bringing as many experts as we can to address these areas. It’s really a distribution of tasks; it’s not just one addressing the political element.

Most importantly, have the citizenry participated in that process, so they understand every aspect of that roadmap to recovery? I think that’s the difference of moving the needle from hope to belief. I want to tell them: It can be done. We have more than a critical mass to start. I really believe that.

Address by His Excellency Reza Pahlavi

Museum of Tolerance, January 30, 2024

Ladies and gentlemen, good evening. I’d like to thank Chairman Cooper, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, No to Antisemitism, and the Museum of Tolerance for their invitation. I am glad to be back at the museum for this important conversation. Only days after International Holocaust Memorial Day, I am pleased to be here with leaders of the Jewish community and particularly our Iranian Jewish compatriots.

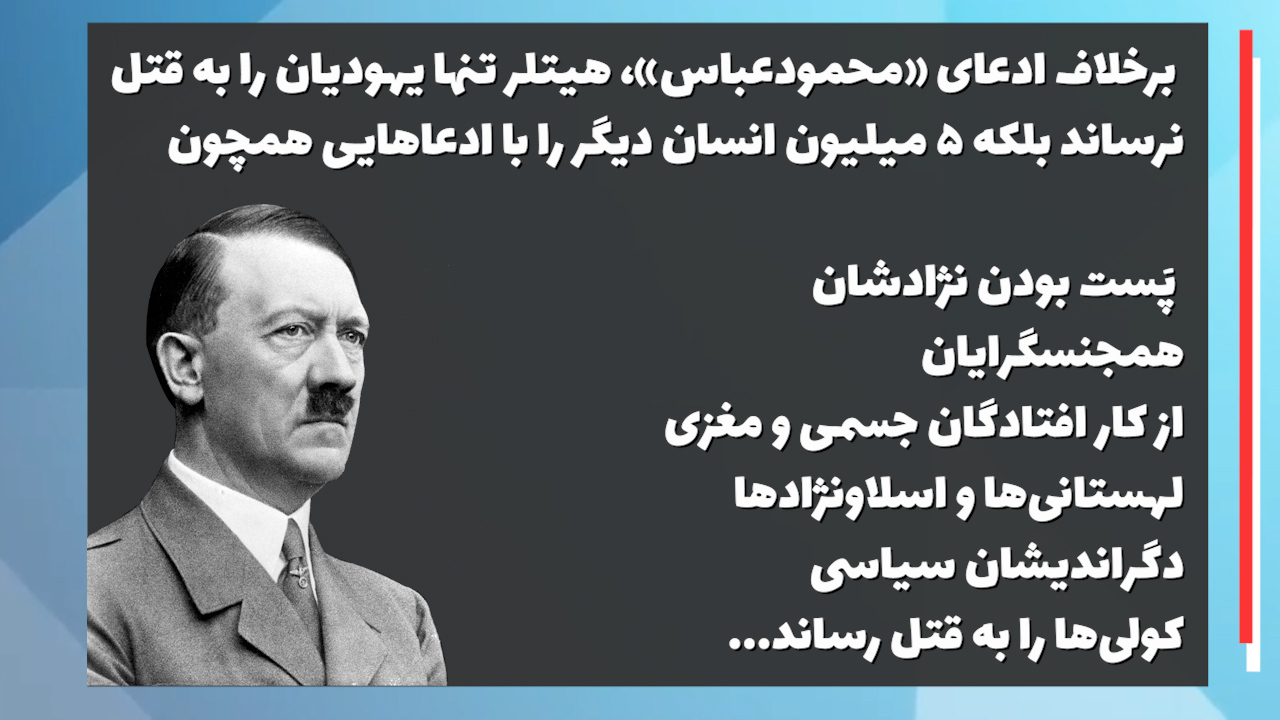

Just four months removed from the massacre of Oct. 7th, we need not be reminded of the continued bloodlust that, astoundingly, many still have for the Jewish people. But walking through these halls is a particularly stark reminder of the grave crime perpetrated by a diabolical regime that the West tried to appease. That appeasement came at the cost of six million Jewish lives, untold innocent civilians, and millions of young military personnel. Regrettably we see that in many circles, the appeasement of bloodthirsty tyrants continues on as a justifiable policy option.

As more innocent people continue to lose their lives to the forces of hatred, allow me to speak in particular to the Iranian Jewish community. For more than four decades, this regime has specifically targeted you, your leaders, and your community. That continues today.

I know you are feeling immense and indescribable pain. I know you have had friends and loved ones stolen from you. I know this pain because I, too, have lived similar personal loss and grief.

You’re looking for answers. You’re looking for solace. You’re looking for peace.

Tonight I am here to remind you that, while many in the world turn their backs on the victims of terrorism and on the Jewish people, the Iranian nation is turning towards you in embrace.

When you see posters with the names of hostages being torn down in cities around the world, remember that Iranians — just as they did after the Sept. 11th attacks — are demonstrating their sympathy and solidarity with the victims and hostages.

When you see the Star of David burned, remember that Iranians refuse to desecrate it and instead hold it high alongside our eternal Lion and Sun flag.

When you see the rape of female prisoners defined as “resistance,” remember that Iranians know the truth because they too suffered the very same fate in the Islamic Republic’s prisons.

When you see all of the hatred, and it feels like you have nowhere to turn and no place to call home, remember that you are part of the Iranian nation. We, your fellow compatriots, share with you this home.

When it feels like you have nowhere to turn, you can always turn home. And know that for anyone who seeks to divide us, Iranian from Iranian, as a secular democratic nation, we shall never permit it.

We extend this same welcome to our non-Iranian Jewish friends. Iranians stand with you in this dark moment. Because even though we don’t share the same nationality, we have a shared biblical history. We Iranians have not forgotten it.

In your rallies across the world, you have seen Iranians standing alongside you and even standing up for you, inspired by the legacy of Cyrus the Great.

Upon my return from Israel last year, speaking to the Anti-Defamation League, I said that just as Cyrus helped liberate the Jewish people from Babylon and aided them in rebuilding their temple, we Iranians, too, have a temple. But an evil, anti-Iranian regime has occupied it and has taken its people hostage.

Iran is our temple. And my friends, we are facing a common enemy.

Indeed, this evil regime is waging war on both of our great nations, Iran and Israel. And just like it did to the last diabolical regime the West tried to appease, this feckless policy is leading to more devastation and destruction across our region. From Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Gaza, to Hezbollah in Lebanon, to the Houthis in Yemen, to militias in Syria and Iraq, our entire region is paying the price for this policy of appeasement. From the refusal to enforce sanctions, to paying ransom for hostage-taking, this policy is not weakening the Islamic Republic, it is incentivizing and emboldening it.

By now it should be clear to all what has long been clear to Iranians: The Islamic Republic is the eye of the octopus controlling all of these tentacles.

Attempting to appease this Goliath is futile. After 40 years, the time has come to give David a chance.

My friends, the people of Iran are the Davids of our time and they are rising up, not only for their own sake but for that of the entire Middle East and the entire world. Despite more than four decades under this regime’s reign of terror, they are not backing down. Indeed, they are doubling down in their fight for their liberation.

The Islamic Republic must go and the liberation army is the millions of Iranians on the streets, paying for their freedom and for peace in the region with their lives. Let us ensure that if they are to make the ultimate sacrifice, they achieve their lofty goals. We can do that by supporting them in their battle, not by sitting on the sidelines.

In more than four decades, I have not sat on the sidelines waiting for miracles. And for many years, it was a lonely path, before today’s courageous Gen-Z on Iran’s streets were even born. But I knew the time would come — and now it has.

“I believe that, just as Iranians of all faiths lived peacefully alongside one another before the revolution, only to see their lives shattered and disrupted, once free we shall once again be a nation committed to respecting and upholding the fundamental freedoms and rights of all our citizens.”

I knew this time would come because I had more than hope — I had belief. Belief in our nation and belief in our people’s resolve. I believe that, just as Iranians of all faiths lived peacefully alongside one another before the revolution, only to see their lives shattered and disrupted, once free we shall once again be a nation committed to respecting and upholding the fundamental freedoms and rights of all our citizens.

In light of such readiness, the world, particularly those whose vital interests depend on fundamental change in Iran, must seize this moment and maximize our chance of success by giving us their full support. I count on you, members of the diaspora, and all friends of Iran, to join us in this campaign for liberation.

Thank you.

Tabby Refael is an award-winning writer, speaker and weekly columnist for The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Follow her on X/Twitter and Instagram @TabbyRefael